In 2020, the incoming president must tax the rich, or risk revolution.

President Donald Trump has never met a problem that he thought could not be solved with a tax handout for the super-wealthy, but as his first term wraps up, the USA needs better solutions.

Contrary to his instincts, the political consensus in the USA, and most other developed western countries is that taxes on the rich should be raised, and methods of tax avoidance eliminated.

When surveyed, comfortable majorities in France, the UK and Germany back higher taxes for millionaires, and in France, the public’s confidence in Macron has never recovered from early tax cuts for the super-wealthy.

Whenever it is proposed that taxes on the richest sliver of the population are raised, alarmist conservatives evoke the slaughter of the Kulaks, and the Ukrainian famine as if similar events may be just around the corner.

However, historical trends have created unimaginable wealth and abundance, even as the market has placed artificial constraints on access to shelter, food, medicine and opportunity: the fall of communism; a 75-year uninterrupted period of comparative peace; and the invention of the internet, all accompanied by easy tax dodges.

In such a climate, any suggestion that government may have a larger role to play in providing well-being for its citizens invariably invites outdated small government ideologies in response.

Thatcher once said: “you know, there is no such thing as society,”, while Reagan opined: “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Such stupid and empty sloganeering from the right marked a pivot away from post-war reconstruction towards laissez-faire economic models and the voodoo economics of trickle-down, and the trends sparked by these shifts are obvious.

Now, Boris Johnson and Donald Trump are the sick punchlines to Thatcher and Reagan’s setups.

Since the new millennium, the super-wealthy friends and allies of conservative politicians have distorted democratic transitions of power with money, and while the DOW Jones has approximately doubled, median wages have stagnated.

Government is not the solution to the problems of the wealthy, but to be frank, their problems are as remote to the average person as are the problems of an extra-terrestrial.

If the super-wealthy think that government is a problem for them now, then that problem will pale beside what may already be replacing it in cities like Portland if they continue to hoard opportunity and wealth.

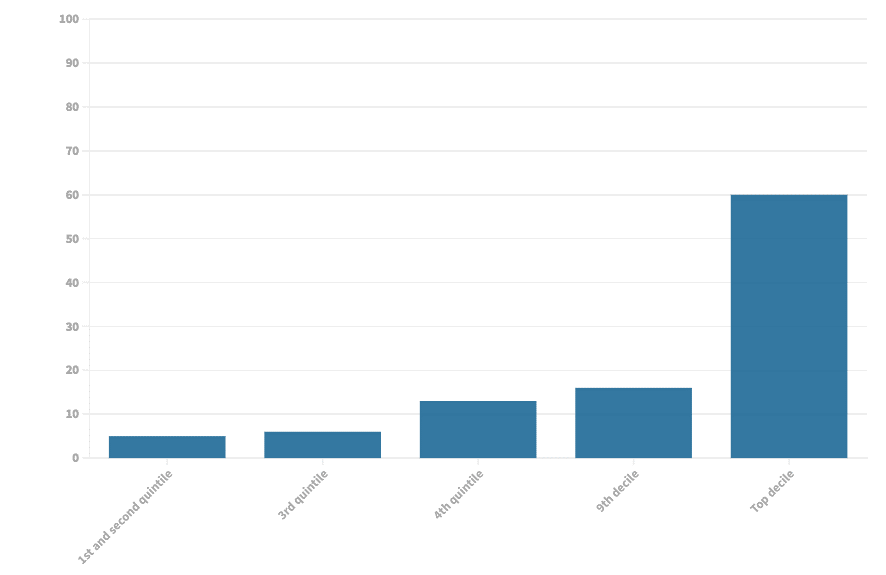

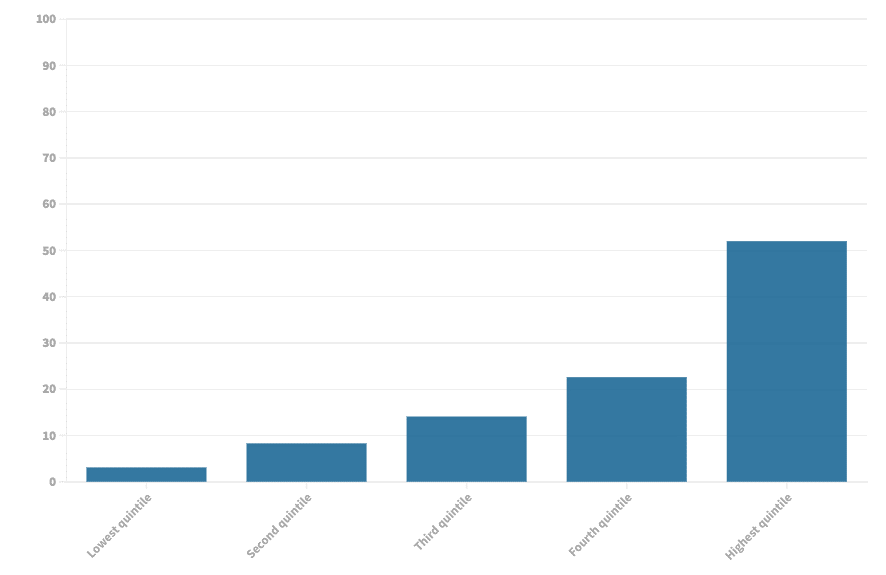

Here are two graphs demonstrating this point: the wealth distribution in France in 1760-90, and wealth distribution in the United States in 2018.

Wealth distribution in France, 1760-1790

Wealth distribution in the USA, 2018

Make no mistake, the ideology of the super-rich is not one iota different from “let them eat cake.” They even announce it openly on occasion.

When Barbara Bush was asked about the – mostly black – victims of Hurricane Katrina, forced to huddle in the Astrodome for shelter after their homes had been swept away, she claimed: “So many of the people in the arena here, you know, were underprivileged anyway, so this, this is working very well for them.”

More recently, and closer to home, Dominic Raab posted a photo of himself smiling at a foodbank. After 10 years of his party’s leadership, the UK’s largest foodbank network, the Trussell Trust, has had to hand out almost 40 times as much food per year as they did when the Conservative coalition was elected.

Such social blunders are sometimes referred to as “tumbril remarks”, a reference to Dickens, who described the rustic wheelbarrows in which haggard, disgraced courtiers were brought to the guillotine, to have their heads taken away in the same carts.

His first mention of them reads thus: “It is likely enough that in the rough outhouses of some tillers of the heavy lands adjacent to Paris, there were sheltered from the weather that very day, rude carts, bespattered with rustic mire, snuffed about by pigs, and roosted in by poultry, which the Farmer, Death, had already set apart to be his tumbrils of the Revolution.”

In light of inequality as stark and bleak as that which prompted the erection of the guillotine at the Place de la Révolution, Elon Musk tweeted: “I bet no one on Twitter even *has* a guillotine! Poseurs …”

Such classist attitudes are even baked into the English language. Consider the terms “noble” and “base”, both derived from the Anglo-French feudal system, then used to describe class, now used to signify moral worth.

Instead of riding his luck and betting on who does or does not have a guillotine, Musk and his equivalents could submit to a slightly higher rate of taxation, especially given that Tesla has hugely benefitted from public-private partnerships.

It seems government is only a problem to him when the public component of the partnership demands to see some return on investment.

Popular left-wing Twitter account @HasBezosDecided, which tracks whether or not Jeff Bezos has decided to end world hunger yet, said of this battle between government and business: “Lenin was writing about this argument in 1917.

“Capitalism cannot exist without the state and the tax required to uphold the state.

“Private ownership of the means of production is upheld by protection from the police and the military.

“Without them, the workers would easily seize the means of production with little to no resistance.”

More sensible solutions are being put forward by serious economists. Thomas Piketty has one of the most extreme policy solutions, suggesting taxes that cap personal wealth at $1bn.

I for one am confident I could find a way to scrape by on a billion dollars, but then I didn’t kickstart Amazon or Microsoft.

Those people do of course deserve rich remuneration for their brilliant ideas, but whether or not they deserve as much as they have is another question. They are great men, but what if anything should that mean for their tax rates?

Many billionaires not in the mould of self-starters like Gates or Bezos are heirs to great fortunes, who inherited their wealth. Musk is one of these, as is the current US president if he is a billionaire at all.

Proposing taxes on these people is often described as the politics of envy, but I see little to envy in them.

Many heirs seem at best bored, or at worst insane, but at the very least, wracked by guilt and feelings of inferiority, even as they fly in private jets and assume career trajectories that many middle- or working-class families could only dream of.

They are often forced to invest disproportionate amounts of energy into hoarding their wealth and warring with their own family members for ever-larger slices of the pie.

If all but $1bn of their fortunes were taxed away, they would still have a billion-dollar head-start on most of the population, and that sort of advantage only tends to calcify with time.

Florence’s highest earners in 2011 included many of the same families as in 1427, according to Italian economists Barone and Mocetti.

Meanwhile, when the late Duke Gerald Grosvenor was asked how a young person could emulate his financial success by the FT, he replied: “Make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend of William the Conqueror.”

If billionaires give up their wealth now, organically, they could stand to personally benefit. Bezos and Gates could frame themselves as the force that kept the western world from starving amidst the worst pandemic for over a century without leaving a dent in their bank accounts.

But, as each day goes by, and they refuse to solve basic problems for millions of struggling working people, public goodwill declines.

Data from European Review of Economic History, 4, 59-83, Cambridge UP, 2000. United States Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018, Report number P60-266. Visualisations created with Flourish.