In a photo of the Oval Office, President John F. Kennedy sits behind the desk on the phone frowning. A navy man, he carried his love of all things nautical with him throughout his life. On the desk are displayed several carved sperm whale teeth, known as scrimshaw.

JFK is perhaps the most famous collector of scrimshaw. His collection, comprising some 37 pieces, featured on tours to foreign dignitaries.

Most tellingly of all was the president being buried with a piece commissioned for him by Jackie, carrying a token of the hunt like a Saxon king.

Scrimshaw can cover any piece carved from ivory, but is most often used to describe pieces carved from the teeth of sperm whales.

THE 37 PIECES: John F. Kennedy in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Examples of the President’s extensive scrimshaw collection can be seen on the desk (image courtesy of jfklibrary.org )

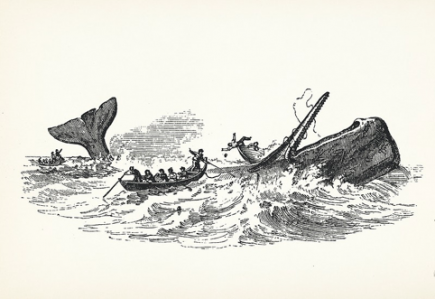

The sperm whale fishery, which intensified in the early 19th century, is infamous for its brutality. In spite of the lethal effectiveness of the whalers, the jobs was nonetheless incredibly dangerous. Some whalers even barred married hands from the more perilous roles due to the risk.

Robin Diaper, curator at the Hull Maritime Museum – which holds the largest collection of Scrimshaw outside the USA – told MM: “Sperm whale catching was very different to the Arctic whaling.

“They’d be away for months whereas sperm whalers from America and London could be away for years because they processed their oil on board.

“The sperm whale teeth became quite valued as part of the bycatch, but it was really important to pass time.

“Whaling is a bit like being at war, there’s very long periods of waiting and captains would have to keep the crews occupied and keep themselves occupied, and this was a very time-consuming pastime.”

The majority of collected scrimshaw comes from this early period, with the mechanised industry of the 19th century not possessing the same romantic appeal as its lance-wielding forbears.

Scrimshaw is as unusual art form, as it was crafted by sailors of all ranks. Some pieces are astonishing in their craftsmanship, others are more crude. Portraits of women are a common subject, often copied from pictures in magazines, as well as likenesses of ships, and of course the whales themselves.

From a historical perspective, the work gives us insight into the minds of the people who underwent these voyages. It is rare indeed to find a form of art which gives an impression of the trials and tribulations of people from throughout society, from the bottom to the top.

For collectors, the romance is undoubtedly part of the appeal. In Moby Dick, when we first meet the Pequod, the ship is described as “…a thing of trophies. A cannibal of a craft, tricking herself forth in the chased bones of her enemies”.

LIKE BEING ‘KICKED IN THE CHEST’

The high risk and reward associated with the sperm whale fishery perhaps also cemented it in the US imagination. Any man could rise to wealth on a whaler, no matter his origins.

Sperm whales were hunted for their oil. Usually whale oil is processed by melting down the blubber to release the fat, however the anatomy of sperm whales made them uniquely unfortunate.

The forehead of a sperm whale contains a large balloon-like organ which they use to project sonar to locate prey and communicate with each other.

Some biologists have suggested that an adult bull sperm whale is even capable of killing a person with sound, and divers who have swum with sperm whales have described how the whales clicking at them feels like being kicked in the chest.

Crucially, the organ contains the spermaceti fluid, which focusses and receives the sonar signals. If handled correctly, a sperm whale can yield up to 1,900 litres of this fluid, in addition to the oil derived from the blubber.

HUNTED FOR OIL: An illustration from Thomas Beale’s The Natural History of the Sperm Whale, next to a photo of Japanese factory whaler Nisshin Maru. (Image courtesy of bluebird-electric.net )

In a tight, profit-focussed business such as whaling, as little as possible was wasted.

“There was no other value to them [the teeth], they were the only thing that didn’t have any sort of commercial value,” said Diaper.

Ironically, the teeth have since become the only part of the sperm whale to continue to be traded. The current world record for a single whale tooth currently stands at over $450,000.

Between 2016 and 2017, the market saw a new influx of pieces as a very large collection came up for sale.

The opportunity showed that interest in scrimshaw collecting is by no means a thing of the past, as over two years the collection fetched $2.1 million dollars at auction.

However, despite the lucrative nature of the objects, some auction houses no longer sell scrimshaw. Christie’s auction house has not sold scrimshaw since 2015, a decision they did not appear willing to explain fully.

Indeed, they appeared very keen to distance themselves from the practice.

“Our specialists carry out stringent due diligence on the provenance of all such objects in order to satisfy ourselves that these strict criteria are met.”

WHALING MORATORIUM

Under UK law, the sale of items made of “worked” ivory, including scrimshaw, is prohibited by the CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) law, which also controls the importing of exotic species.

Under this, a piece may be sold if it can be proven that it is an antique. In 2013 the European Commission introduced new regulation which reset the parameters of what constituted “worked”. New regulation also requires a certificate to authorise the sale of such an item.

The law is primarily designed to restrict the sale of elephant ivory in order to protect populations from poachers.

The interest in scrimshaw, whilst controversial in its own right, does not carry the same direct risk to living animals since the International Whaling Commission, a body originally set up to regulate the industry, imposed a moratorium on all commercial whaling in 1982.

The last sperm whales to be commercially hunted were killed by Japanese whalers in 1988, as Japan flouted the moratorium it viewed as too draconian.

Whilst illegal whaling does happen, it is mostly carried out by the fleets of whaling nations trying to put pressure on the IWC to lift the moratorium, such as Japan’s controversial forays into the Southern Ocean, and its eventual decision to leave the IWC and resume commercial whaling in domestic waters in 2019.

Even Japan, the most militant pro-whaling country, mostly confines its hunts to species categorised as “least concern”, although it has also been revealed that it has also targeted the endangered sei whale, the third largest species.

Sperm whales at least remain spared from commercial whaling, and the challenges of the industry make it far less likely for poachers to attempt to hunt sperm whales for their ivory than elephants or rhinos.

Art historians have raised their own concerns about the way CITES law works, arguing that it is too broad in its scope. A blanket ban on all private collecting of ivory could result in the confiscation and destruction of many historically important pieces of work.

ZERO COMMERCIAL VALUE: Examples of scrimshaw – which ironically initially had little net worth – from the collection of Hull Maritime Museum. (images courtesy of Hull Maritime Museum, with thanks)

In 2018, Dr. Janet West, an art historian specialising in scrimshaw, wrote a letter to the Financial Times detailing her concern.

“I agree with Martin Levy that the British Museum was right to accept the Victor Sassoon ivories collection,” she wrote.

“Although the ivory bill aims primarily at commercial dealing in elephant ivory items, it will allow other CITES ivories to be brought in later.

“These include sperm whale teeth and walrus tusks with scrimshaw images resembling engravings, some of them of great artistic merit. Many of them show whale-ships from the age of sail which are often the only known pictorial representations of individual vessels.

“A detailed study of some early 19th-century scrimshaw revealed unusual rigging not previously recorded.

“There is a strong lobby to ban private ownership of any ivory. Much fine scrimshaw is of British origin but owned by private collectors, and is therefore at risk.

“It would be tragic if these artistic sources of potential historical information were to be lost through legislation that would have no appreciable benefit to the existing world population of marine mammals.”

AUCTION FRENZY

Even under current regulation, collectors must be very careful to avoid falling afoul. In the US too, where collecting scrimshaw is more popular, it is illegal to ship scrimshaw across state boundaries.

Instead of a blanket ban, the focus could be on ensuring that antiques are correctly identified, and cracking down on fakes and reproductions made from ivory harvested from poached animals.

Christie’s would not go into the reasoning behind their decision to stop selling scrimshaw. However, given the sheer quantity of antiques made from questionable materials, the brutal history of the whaling industry is unlikely to be the only consideration.

Rather like whaling, sales of major scrimshaw collections appear to be sporadic, with long periods of no desirable examples being available punctuated by a frenzy of auctions after a renowned collection comes up for sale.

The importance of scrimshaw as a source of historical knowledge is not in doubt, but it begs the question as to whether it is appropriate for items coming from such an unpleasant period of history to be bought and sold, and held in private collections away from the eyes of researchers.

It is clear that despite trading in scrimshaw until relatively recently, auction houses are now less willing to allow themselves to be mixed up in this trade.

However, flaws in the way scrimshaw and other antiques made from ivory are regulated puts historically valuable items in private collections at risk.

JFK used his scrimshaw as a way of expressing the American ideal. Forbearance, strength, and patience combined to create a bounty of prosperity, reward for the perseverance through hardship.

Now however, it serves as a reminder of how fraught our relationship with nature continues to be, and how inadequate our responses often are to ensuring its survival.