With the hustle and bustle of today’s society, it can often be easy to miss things as you go about your day to day business.

Manchester’s Piccadilly Gardens is a popular place for everyone in the city, whether you pass through it on your way to work, want a tranquil place to eat your dinner or are indulging in a bit of retail therapy in the area.

The large open space is home to a number of statues depicting some great figures in this nation’s history, with Mancunian Matters looking at who these people are and the history behind the monuments creation.

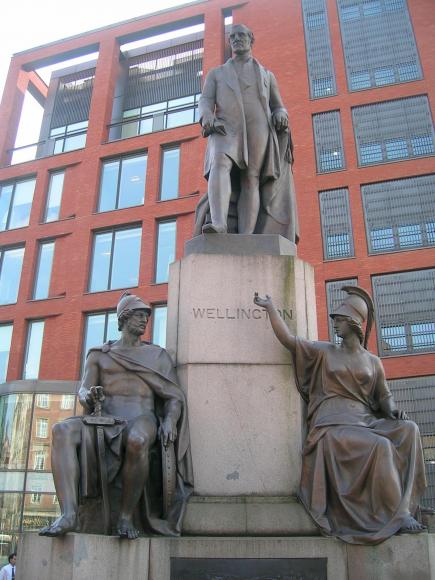

Duke of Wellington (1769-1852)

Arthur Wellesley, or the 1st Duke of Wellington, was a former Prime Minister, but is more notable for his triumphant military career and role in the Battle of Waterloo.

Born in Dublin in 1769, Wellesley signed up for the army at 18 and fought in campaigns at Flanders in 1794, and India in 1796.

His efforts saw him awarded a knighthood in 1805, with further campaigns in Portugal and France leading to his promotion to Commander of the British Army in the Peninsular War.

The title of Duke of Wellington was bestowed on him in 1814, with his finest hour being his leadership during the closing stages of the Napoleonic Wars, which included a decisive victory at Waterloo in 1815.

On his returned to Britain he was paraded as a hero, and became Prime Minister in 1828.

During his time in politics, Wellesley served as Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Lords in Sir Robert Peel’s government, but retired in 1846 and died in 1852.

Along with Victoria, statues of the Duke of Wellington are popular across the country, including Wellington Arch in London’s Hyde Park.

Piccadilly’s bronze statue, sculpted by Matthew Noble and erected in 1856, stands proudly surrounded by four smaller allegorical figures representing war, justice, peace and victory.

They sit on a marble base which also contains bronze depictions of key moments from Wellesley’s life, including scenes from the battlefield and his time in politics.

Queen Victoria (1819-1901)

Queen Victoria, one of the most recognisable monarchs in British history, was born at Kensington Palace in 1819, and became Queen aged 18 in 1837.

During a reign that lasted almost 64 years – the longest for a British monarch until it was surpassed by Elizabeth II in 2015 – Victoria became synonymous with the golden years of empire, adopting the title Empress of India in 1877.

By the end of Victoria’s reign, Britain’s oversees empire stretched over roughly one-fifth of the earth’s land mass, with almost a quarter of its population under British possession.

As well as her duties as Queen, Victoria was a devoted wife to her husband Albert, whose death in 1861 sent her into depression and led to her to wearing only black in memory of him.

The statue of Victoria in Piccadilly Gardens Victoria was originally conceived to celebrate spending sixty years on the throne, however the Queen passed away in 1901 before it was completed.

Edward Onslow Ford was commissioned to create the sculpture, and initially wanted to carve it out of marble.

Victoria however felt that the material would not be best suited for the smoke-heavy air conditions of the Manchester atmosphere, meaning that the unveiling of the statue was delayed by 10 months, in which time she sadly.

The statue is topped with a figurine of St George on horseback slaying a dragon, with inscriptions reading:

Erected by the citizens of Manchester in 1901 to commemorate the completion in 1897 of the sixtieth year of her reign.

&

Let me but bear your love, I’ll bear your cares.

James Watt (1736-1819)

James Watt was a highly talented Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer, whose work fundamentally improved steam engine technology which played an integral part in the industrial revolution.

Born in 1736, he worked as an instrument maker at the University of Glasgow, and when he was tasked with repairing a Newcomen steam engine, he realised they wasted huge amounts of energy.

By devising a separate condensing chamber, he managed to greatly improve their efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

After going into partnership with Matthew Boulton in 1775, Watt began to mass manufacture his version of the steam engine, and Boulton & Watt became the most important engineering firm in the country, effectively driving the revolution.

By his death in 1819, Watt had also developed the concept of horsepower, with his legacy being a unit of measurement for electrical power – the watt – named in his honour, as well as being immortalised in print on the reverse of the current £50 note.

Although not a Mancuniun, it was through Watt’s improvements to the steam engine that Manchester became a huge manufacturing city.

It was because of this that he was chosen to be cast in bronze by William Theed in 1857, who also created the statues of John Dalton in Chester Street, and Humphrey Chetham in Manchester Cathedral.

The statue is a replica of one that stands in Westminster Abbey, and originally sat alongside one of John Dalton, which now stands at the entrance to the Royal Infirmary after being moved there in 1908.

Robert Peel (1788-1850)

Born in Bury in 1788, Robert Peel twice served as Prime Minister for the Conservative party, and is widely regarded as the father of the police force.

The son of a wealthy cotton mill owner during the days of Manchester’s booming textiles industry, Peel entered parliament in 1809, and after becoming home secretary, he oversaw the creation of the Metropolitan Police.

The terms ‘bobbies’ and ‘peelers’ are derived from his name.

In 1834, Peel became Prime Minister for the first time despite having a minority in the House of Commons, and due to the difficulty of this situation, he resigned a year later.

In 1841, Peel again became Prime Minister and had initial success in passing both the 1842 Mines Act forbidding the employment of women and children in mines and the 1844 Factory Act, limiting working hours for women and children in factories.

As his term progressed however, he struggled in his efforts to repeal the Corn Laws in order to help an Ireland ravaged with the potato famine, and after it was finally passed in 1845, he resigned from government.

In 1850, Peel suffered a bad fall from his horse, and as a result died of his injuries.

A statue of him was cast in London in 1853, three years after his death, and then transported to Manchester to stand proudly in Piccadilly Gardens.

It was created by William Calder Marshall, and is one of a number of statues of the former Prime Minister across the country, with other notable designs on display at Liverpool’s St George’s Hall, Salford’s Peel Park and London’s Parliament Square.

The figures either side of Peel represent Manchester and its textiles history, and the other depicting industry and the arts.