When Nat Griffin left Manchester Airport for Palestine’s West Bank, he was hoping for an opportunity to do some good. But when Israel attacked Iran on 13 June, the latest escalation in a conflict spanning generations, it became apparent that things weren’t going to be so easy.

“I had to be back at the border in three hours, and I was in stuck in the middle of the desert.”

Luckily, there was a car in the distance. They stopped to ask what was going on – an elderly Israeli couple.

“I’m a backpacker. I’m stuck; can you give me a lift to the border?”

“A backpacker?” said the driver. “Crazy time to be doing a thing like that!”

Nat conceded the truth of this. It wasn’t the first time he’d heard it.

“Get in though, we’ll drive you there.”

They got chatting in the car. Nat was a little wary, naturally. However, he wasn’t the first one to broach the topic.

“I think what our government is doing is mad,” said the driver.

“It’s not nice, all the children being killed in Gaza. But our enemies are hiding behind them, I suppose they have no choice.”

They were mostly silent for the rest of the journey.

This was how Nat’s first – and likely, final – trip to the West Bank ended, only five days after it began.

Nat wasn’t really a backpacker, of course. He’d travelled to Israel not for a jaunt, but to meet up with the International Solidary Movement (ISM), a Palestinian-led organisation providing grassroots support to Palestinians in the West Bank.

Nat first love was politics. At only 19 he was selected as the labour candidate in his local council elections. He didn’t win, but he was making a name for himself.

But following the fall of Corbyn and the re-orienting of the Labour party under Starmer, Nat was given the boot. By this point he hardly cared – the party no longer stood for anything he was interested in.

He spent a year splitting his time between the UK and France, getting involved in French politics, but with the surge in popularity of the French far right under Marine Le Pen, this too began to feel hopeless.

Now 26, Nat recently conceived the idea of going to Palestine – leaving protests behind in favour of direct action, he could make a tangible difference in people’s lives without the distractions of party politics.

Nat on the road

Crossing back into Jordan was a breeze compared to the three attempts it took to get into Israel – spread over three days, including a nine-hour stint in an interrogation room at the King Hussein Bridge border crossing.

“It’s crazy to be visiting as a tourist – it’s so dangerous,” said the guard.

“But I’ve been to Pakistan – that was dangerous too.”

The guard agreed that it was.

“Ok, let me have a look at your phone.”

This is where the difficulties began. This wasn’t a case of Nat having downloaded a dodgy meme à la the recent J.D Vance fiasco. Rather, it was what wasn’t on his phone that concerned them.

“You don’t have enough messages on here. You’ve been deleting them, haven’t you?”

“No.”

“You’re lying. We know you’re planning to meet up with someone.”

Despite his protestations, the border guards didn’t trust Nat’s story. They put him on a bus back to Jordan.

Nat spent a few days back across the border, visiting the Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan’s capital Amman. The refugee sections are so old that they’re indistinguishable from the rest of the city – you can’t tell where one starts and the other ends.

These camps were founded after the beginning of the ‘Nakba’ – the displacement of Palestinians after the creation of Israel – in the late 1940s. Many of the people in them were born and bred in Jordan, never having been to Palestine themselves. Unless you knew otherwise, you wouldn’t be able to distinguish them from the other streets in the city.

The Jordanian Palestinians form a part of the larger Palestinian diaspora, which is more varied than many people realise. While Palestinians are predominantly Sunni Muslim, there are other significant religious populations, including Shiite Muslims, Greek Orthodox Christians, and members of the Baháʼí faith. Palestinians were some of the first people to take up the Baháʼí faith, two of its holiest sites – Acre and Haifa – being located on former Palestinian territories.

There are other complications, too, as Karen Howell, chair of the Britain Palestine Friendship and Twinning Network, pointed out to me.

“It used to be, for Gaza, quite stressful, because a lot of Palestinians were working for Israeli companies. Earning good money, too.

“Some have made very good Israeli friends, many of whom are quite devastated with what their government is doing.”

According to polls from last year, about 19% of Israelis believe the government’s response went too far.

And even amongst Israelis, there are tensions. Many of the Israeli settlers in the West Bank are neither Palestinian nor native Israeli – a fact that hasn’t gone unnoticed.

“A lot of the Israelis themselves condemn what the settlers are doing,” said Howell.

“The Israeli government offer foreigners less taxes, free accommodation – all sorts of incentives to come and live in the settler camps.

“Then you’ve got the Israelis that pay taxes asking ‘why is this happening? It’s one rule for them and another for us.’”

Nat made another attempt at getting into the Israel the following week, fairly certain he’d instead be given a lifetime ban. This time he headed south to the Wadi Araba crossing, near the northern tip of the Red Sea.

“They were very suspicious of me. I decided not to mention that I’d already been denied entry unless they asked me.

“All my stuff was searched with a fine-toothed comb – trousers down and everything. They let me keep my boxers on at least.”

“After this, I sat in the waiting room for a while before the guard came back in with two other guys, one carrying an assault rifle.”

The main guard started shouting:

“You know I can smell bullshit on people? Why didn’t you tell me you’d tried to get in before? Who are you working with? Who sent you?”

After another round of questioning, the guard returned with a stamped card and asked Nat to move onto the next stage of the process. This turned out to be another interview, where a woman asked him the exact same questions the last group had asked him.

He was then sent to an office with an older gentleman who repeated the questions for a third time, this time with the added threat that if he even suspected Nat of lying, he’d ban him for ten years.

He asked the same questions. Nat gave the same answers. This time it was enough.

“You can come in for five days. If you stay any longer than that, you’re banned for life.”

Nat’s permit

Nat’s plan was to meet up with ISM, where he’d be given a short training camp before being sent to an as-yet undisclosed location. His role would be to accompany Palestinians on their day-to-day activities, his very presence as a westerner providing a deterrent to potential Israeli aggression.

Mariam, from the ISM communications team, confirmed this.

“It’s a deterrent, that’s what the Western passports do.

“Volunteers use their privilege as a deterrent.”

The ISM was set up during the second Intifada – a major Palestinian uprising in 2000. Where once they had a presence in all major Palestinian territories, since the blockade on Gaza, they’ve mainly been confined to the West Bank.

“These days its predominantly rural areas,” said Mariam.

“The main resistance is just staying on the land.”

Volunteers have been injured before, even killed. In 2024, a 26-year-old American-Turkish woman, Ayşenur Eygi, was shot by an IDF sniper while protesting near the Israeli outpost of Evyatar. Israel claims that Eygi was shot during a ‘violent riot,’ although this claim is strongly disputed.

Nat with some Palestinian children

Since October 7th and the re-escalation of the conflict, the ISM has been struggling.

“We need more activity on the ground,” said Mariam.

And, since the beginning of the war with Iran, the struggle to get people into the West Bank has been even more severe.

“This period of the war with Iran has been challenging.

“People have managed to travel, but we very much need more people to travel.”

Nat can attest to this. His five-day visa didn’t provide him the time necessary to meet up with the ISM, let alone help them.

Nat instead used his five days to get the lay of the land, hoping that his travels could come in handy for a potential later trip, his current good behaviour entitling him to a longer stay.

“I went to Jerusalem. I’ve never visited somewhere with such as gulf between aesthetic beauty and terrible atmosphere.”

He explored for a while, getting lost in the underground streets of the old city.

“It’s like a piece of history brought into the present day, completely out of time.

“But then you go round a corner and see a big flag saying: ‘make Gaza Jewish again.”

He describes an atmosphere of tension in the city, the only smiles coming from shopkeepers, desperate for customers. The tourism industry hasn’t been so good recently, due to the war, and they could use the business.

Nat isn’t too keen on the wares, however – yarmulkes with Donald Trump’s face on them.

Nat then went to Bethlehem, staying just outside the city at the Dheisheh refugee camp. The family he was staying with were relatively wealthy, but this didn’t provide much in the way of safety.

His host told him about how, a few months prior, his house had been broken into by the Israeli military at 3am. They forced him to the floor in front of his family and started searching the house for anyone who might be hiding. This kind of thing happens almost every night.

The streets of the camp are lined with paintings of every resident who has been killed. Nat’s host knows them all by name.

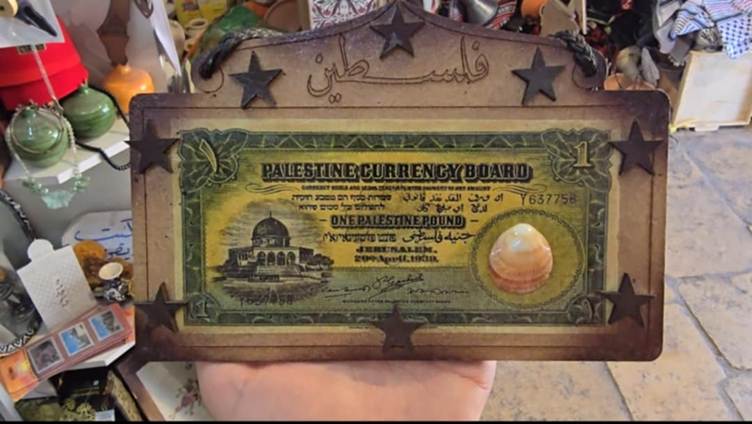

Old Palestinian money

Nat’s final stop was Hebron, the largest city in the West Bank. Hebron has a Palestinian settlement at its centre, as well as at the outskirts.

In 1994, an American-Israeli man called Baruch Goldstein went into a Mosque in Hebron with an assault rifle and opened fire, killing 29 people and injuring 125 others.

Everyone, including then Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and future Prime Minister Benjamin Netenyahu, was quick to condemn the actions, distancing themselves from the slayings.

Fearing reprisals, the Israeli government banned Palestinians from certain streets in Hebron, including Al-Shuhada Street, which had once been a main commercial thoroughfare. Only Israeli citizens or settlers were permitted to enter (and foreign tourists), a prohibition that exists until this day.

This makes travel very difficult for the local Palestinian population, who now have to travel around the city, rather than through it. The ban on Palestinians entering certain streets is strictly enforced, complemented by modern technology.

“I saw an AI machine turret monitoring the street,” said Nat.

“If it recognises your face as that of a troublemaker it shoots you on the spot.”

Young men won’t even pray in certain mosques as they tend to get grief – they’re considered more dangerous than their elderly counterparts.

He had two guides showing him around the town, independently of one another. Both separately confessed that they wouldn’t have dared enter those areas without Nat being there.

“Isn’t it crazy? They, the locals, felt like they needed me to be there for their safety.”

After Hebron Nat only had a day to get back to the border. After crossing back into Jordan, he spent a couple of days planning his next trip. Unfortunately, Israeli customs weren’t having it – on his next attempt to cross the border, he was denied access and given a lifetime ban.

His attempts to volunteer had been effectively neutralised. Five days wasn’t enough time to do anything useful, and he wasn’t going to get another chance – they were suspicious of his persistence.

It put me in mind of something Karen from the Twinning Network told me when we spoke.

“Our organisation helps Palestinians feel less isolated. They know there’s a group with them in the UK, so they aren’t alone.”

But with the incredible difficulty of getting into Palestine, and in many circumstances, the difficulties of getting out; with the roadblocks, the raids, and the ever-diminishing size of the settlements on which on which most Palestinians live – on the outskirts of towns they used to call their own – isolation is exactly the feeling Israel seems determined to produce.

And as it stands, they’re succeeding.

Pictures courtesy of Nat Griffin