When pop behemoth Adele released her fourth studio album 30 in November, she made a request to streaming services – and, more specifically, Spotify.

Change the way albums are automatically consumed on your service. Remove the shuffle option as the default mode of streaming an album. Make the listeners absorb the product as it was intended.

The company obliged, and now when music-lovers hit play on any album page, they hear the tracklist in its officially-released order.

When the news broke, Adele tweeted: “We don’t create albums with so much care and thought into our track listing for no reason. Our art tells a story and our stories should be listened to as intended.”

Spotify responded with a tweet of its own: “Anything for you”, accompanied by prayer hands and a sparkle emoji.

But was this a case of Adele identifying a real issue in the music industry, or more an indication of how our listening habits have changed in the digital age?

Music journalist and critic Annie Zaleski believes it to be the latter.

She said: “I think (the announcement) was an acknowledgment that people consume music in fundamentally different ways now, and technology has made it a lot easier to put together your own version of an album.

“There’s a long history of people taking matters into their own hands – think mixtapes, mix CDs and MP3 playlists – but streaming platforms make it much easier to do this.”

And the way streaming services make it easier is through playlists – collections of songs from a wide variety of artists to suit a particular mood, event, or activity.

Spotify-curated playlists – ranging from ‘The Most Beautiful Songs in the World’ and ‘Throwback Thursday’ to ‘Metal Essentials’ and ‘Rap UK’ – have racked up millions of followers and allow listeners to discover new artists and songs at the touch of a button.

Regular users, too, have the chance to make their own collections of songs and share them with the world.

This might explain why the automatic way of consuming an album had been at random instead of in its official order throughout Spotify’s existence up until Adele’s request was granted, as it would tie in to their promotion of algorithmically-generated playlists.

This has meant that, for many people, consuming an album has now become a passive listening technique rather than an active one.

You can put an album on in the background on shuffle, and then pick the individual songs you like and discard those you don’t, rather than fully immersing yourself in what it has to offer, should you so choose.

A lot of musicians have realised this and have adapted their marketing policies for their new bodies of work accordingly.

As one example, Canadian superstar Drake promoted his 2017 effort More Life as a playlist, stating in an interview with Complex that he wanted it to become the “soundtrack to your life.”

But a marketing strategy that could seem to go against what many perceive to be the fundamental principles of an album isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

As Zaleski said: “I think the definition of ‘album’ has evolved and become much more amorphous today, which is exciting.

“Albums are more musical projects than a discrete release. We’ve been moving that way for a while now, but in recent years it’s become more common.”

However, the greater focus on playlists and individual songs has led to album sales experiencing a noticeable dip in recent times, not least because streaming has also become the dominant platform on which to “buy” an album.

This is reflected in the number of albums that have received a platinum certification within the year they were released.

Excluding compilation, film soundtrack, and live albums, 23 albums that were released in 2000 went platinum in England (sales of 300,000 copies) before the year was out, and in 2006, 41 separate albums repeated that feat.

But only nine LPs that have been released since 2018 have managed to shift 300,000 combined units – with streaming, downloads, and physical copies all now taken into account – within their original release year.

It’s a similar story in the USA, too.

Every year barring one from 2000-2006 saw more than 40 separate albums hit the platinum certification mark – namely one million units – before the year of its release concluded, at a time when the album was seen as the fulcrum of the recording industry.

But these figures have tailed off drastically, and only one year since 2010 has seen more than ten albums released that year go platinum before a new year dawned.

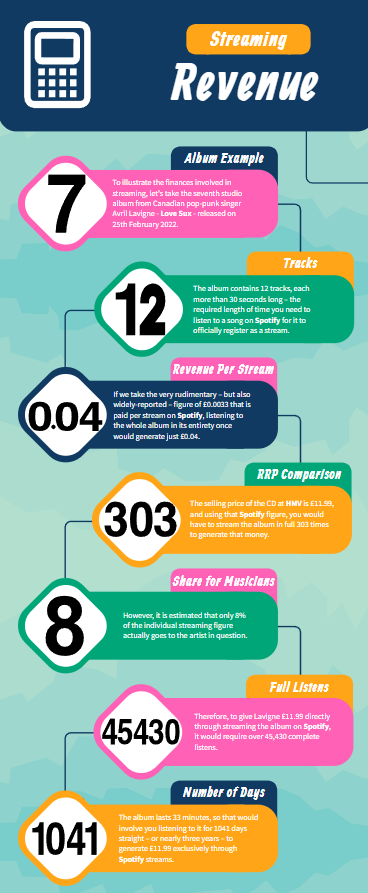

Furthermore, the low finances on offer to musicians from streaming emphasise another negative aspect of the music industry during the digital age.

Here is an example of how long it could take for a musician to make a certain amount of money through album-streaming on Spotify alone, using widely-reported streaming payment figures.

These low finances point towards a greater need to get the right song for a high-profile playlist rather than a complete package.

Zaleski says this has led to more musicians – irrespective of popularity – changing their release strategies and putting out singles well in advance of their album, so that they get their own “distinct promotion push” and “listeners have heard more of an album.”

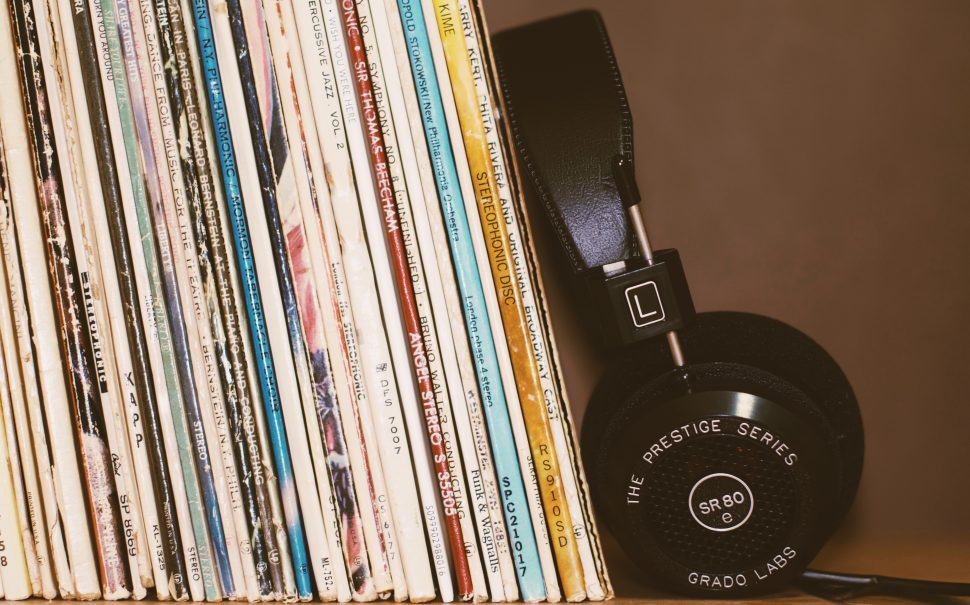

But even in the playlist age, there is still a huge market for albums, illustrated most prominently by the resurgence of vinyl over the past two decades.

Annual vinyl sales figures in the UK have risen every year since 2008, and they reached yet new heights in 2021 when the British Phonographic Industry revealed that more than five million vinyl albums had been purchased throughout the year.

Zaleski believes this resurgence is due to people wanting a form of art which is “tangible” and real.

“It’s almost like a rebellion against the digital-heavy age,” she said. “It’s a throwback to a time when you really had to work hard to hear music, rather than access millions of songs with one click.”

But it isn’t just older records that dominate the vinyl charts.

Adele’s 30, Ed Sheeran’s =, ABBA’s comeback effort Voyage (which broke the record for first-week vinyl sales upon its November release), Lana Del Rey’s Chemtrails Over The Country Club, and Wolf Alice’s Blue Weekend – all of which were released in 2021 – featured in the top ten biggest-selling vinyl albums last year, according to the Official Charts Company.

They took their place alongside Fleetwood Mac’s classic 1977 album Rumours, the late Amy Winehouse’s 2006 LP Back to Black, Queen’s Greatest Hits compilation,and Nirvana’s breakthrough 1991 effort Nevermind.

Zaleski does not find this blend surprising. She added: “Because of streaming, younger generations have a much easier time accessing bands and artists from all eras.

“The generational divide between genres has dissipated.”

So it seems clear that whilst the playlist has revolutionised how music is consumed in the age of immediate accessibility – for reasons both good and bad – it has not taken over the music industry completely, and doesn’t seem likely to anytime soon.