South Manchester girl Beth Palmer had the world at her feet. A talented musician, fiercely independent and incredibly popular. Above all she was a loving daughter – adored by her father Mike. But when lockdown arrived her world was turned upside down.

Some of her gigs were cancelled, and she didn’t know if she’d be able to finish college. Tragically this burden became too much – she took her own life at the tender age of 17.

Mike Palmer said: “Growing up she was the most wonderfully loving girl, I couldn’t have wished for a better daughter. She was a little girl who used to sit on my shoulders and daddy this daddy that.

“She could have gotten away with anything, she was quick and sharp witted. She could say anything and she would get away with it because afterwards she would go ‘I love you Dad’.”

Data presented by the ONS suggests that suicide rates have fluctuated over the past two decades and Beth was, tragically, part of an uptick around 2020 when the pandemic took hold. The continuation of post pandemic stress has led to suicide rates continue to rise significantly above their 2019 level.

It is important to note that the ONS data comes with some limitations. It records suicide registrations, which may happen the year after the death itself – or even later. Some local authorities, including Bury, whose councillor Ayesha Arif spoke to MM, use coroner statistics which record the death date instead.

Additionally, nationally suicide rates have ebbed and flowed around the 10 deaths per 100,000 over the last twenty years highlighting the cause are multifaceted.

But the arrival of the pandemic appears to have made a clear impact, with rates peaking at an unprecedented 10.5 deaths per 100,000.

Beth’s hometown of Manchester bore witness to this unsettling trend.

In the pre-pandemic era, suicide rates in Greater Manchester were at an all-time low, with the area seeing 9.6 suicides per 100,000. However the sudden onset of the pandemic meant the city dealt with a surge in suicides, witnessing a troubling 4.12% increase compared to 2019.

A Samaritans spokesperson said: “Suicide rates remain unchanged but we know suicide can be prevented.

“It’s vital that anyone struggling to cope doesn’t feel alone with their challenges and they seek support before they reach crisis point.”

The intricate nature of suicide means there’s never one cause and there is always a multitude of factors at play. But the pandemic proves that particular issues can have a devastating effect.

The impacts of the pandemic

“Beth asked me, ‘How long will this last, dad?’ – and I said three months,” said Mike. “I didn’t feel the pressure of it. But Beth as a young person did.”

England and Wales saw a harrowing rise in the number of suicides during the pandemic as numbers reached an all-time high and 2% higher than pre-pandemic numbers and over 11% higher than statistics from 10 years previous.

According to the ONS data Greater Manchester saw an increase in recorded suicide of over 4% pre-pandemic numbers and at the height of the pandemic in 2021. This change was particularly noticeable in Trafford which saw a 36.76% increase over this period with Bury and Manchester also producing staggering increases.

However, the elusive nature of the causes of suicide meant this trend was not noticeable across all Greater Manchester boroughs, and Tameside, Bolton, Stockport and Rochdale all saw a decrease in this time period.

Sadly the legacy of this lives on, as the impact of a relentless strain of financial burden exacerbated by a soaring cost of living. The data presented demonstrates only a small decrease post pandemic, a drop of 0.8 deaths per 100,000, with all regions continuing to rise except Salford and Oldham. This was most noticeable in Rochdale, which has seen numbers rise by 20% in this period. Only two boroughs, Salford (-4.17) and Oldham (5.68%) have seen numbers drop post-pandemic.

Additional factors

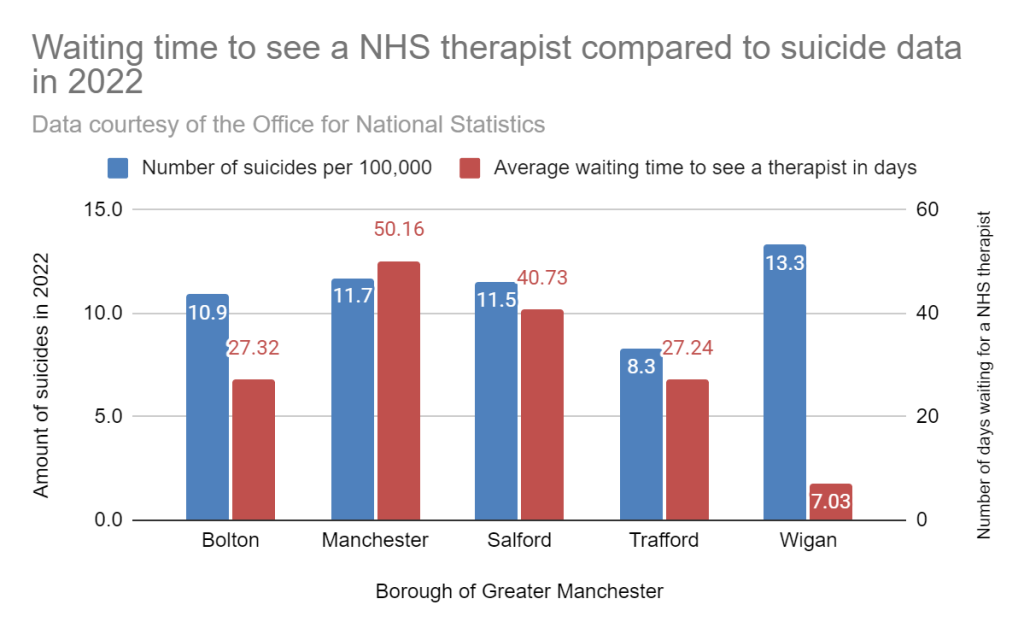

The Covid pandemic cast a shadow over essential mental health services, exacerbating existing challenges. Recent data underscores the strain on these services, revealing significant delays in access to therapy across Greater Manchester.

Between 2018 and 2023, the average waiting time for individuals awaiting their first appointment with an NHS therapist surged by 40% across the region. Notably Wigan experienced an alarming 208.87% increase in waiting times during this period, reflecting the escalating demand for mental health support.

However, the extended wait for mental health services did not correspond to an increase in suicide rates.

Cllr Arif said: “Rates have remained relatively stable over the last 10 years as have the demographics of those dying by suicide.

“We continue to see the highest rates of suicide in males 45-65, with key themes highlighted in coroners’ reports including mental health, substance misuse, bereavement, long term health conditions, under police investigation and relationship breakdowns.”

These findings underscore the intricate dynamics at play within the mental health landscape, challenging assumptions about the direct relationship between services and suicide prevention.

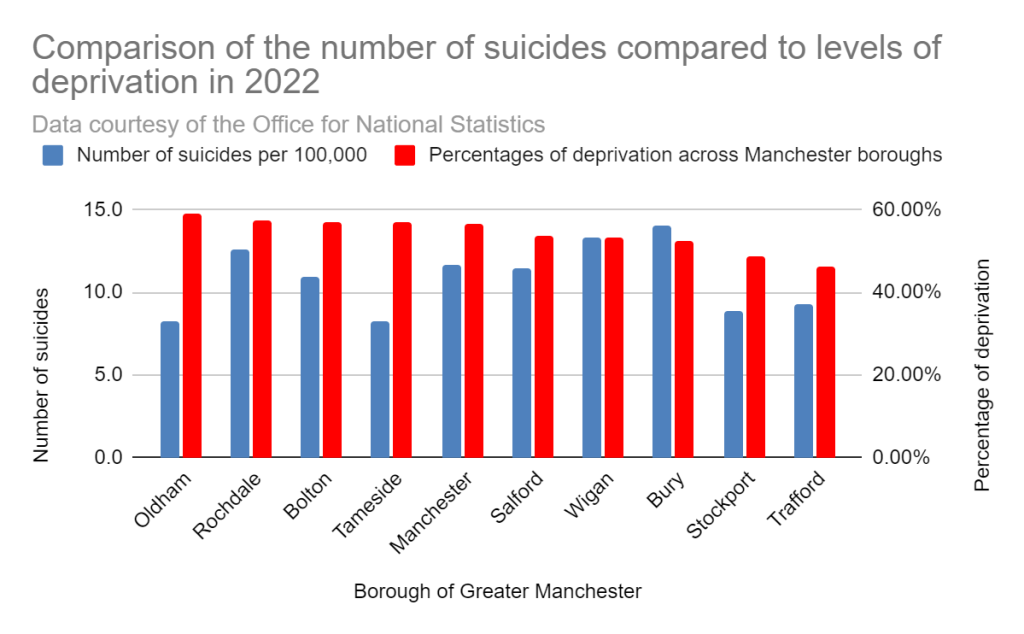

When discussing suicide rates, the role of deprivation has long been a focal point – the assumptions being there is a link between higher levels of deprivation to increased suicide rates.

However, ONS data on deprivation challenges this understanding. Comparing the ONS’s measurements on four dimensions of deprivation – education, employment, health and housing – to the ONS suicide data revals discernible link between the two measures. In fact the correlation coefficient between deprivation and suicide rate stood at 0.05, suggesting a negligible relationship.

The data highlighted the regional disparities. For instance, despite boasting the highest percentage of deprived individuals at 59.1%, Oldham reported the lowest recorded suicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants in the region standing at 8.3. Conversely, despite Bury ranking third in terms of deprivation levels, it registered the highest suicide rate per 100,000 (14).

Cllr Arif said: “We have seen a significant increase in demand in recent years for mental health services, particularly in children and adolescent mental health.

“We have a whole raft of services in place to support those experiencing mental health issues, from grass roots community groups to support those with low level mental health issues, to high level medical support for those with severe and enduring mental health issues.

“As such we have seen a significant reduction in our waits across a number of our services.”

These findings challenge entrenched perceptions regarding the interplay between socio-economic disadvantage and suicidal behaviour, underscoring the complexity of factors influencing mental health outcomes.

What next?

“Losing Beth absolutely shattered me,” said Mike. “To lose my little girl like that reduced me to nothing and it felt like I was under the ground. I became suicidal myself and basically wanted to die.”

Following his daughter’s death Mike found comfort in a group of three fellow fathers who had lost their child, known as the Three Dads. Through the solidarity established in one another they have fundraised for the 24/7 helpline Papyrus Prevention of Young Suicide whilst raising awareness of the importance of having difficult conversations.

Mike offered advice to those who see a close one suffering: “Act. Don’t ignore it. Encourage talking.

“If you think someone is in such a place that they are considering taking their own life ask them: Are you thinking of suicide.

“It’s a very hard question but the training shows that if you ask the question, an answer back is often an honest one and then you can act and say there is no magic wand here but doing nothing is not an option.”

A key focal point of the Three Dads campaign is a petition, intent on changing the school curriculum to raise awareness of suicide from a young age, which raised 160,000 signatures and was debated in parliament.

“What we learnt on the first walk is that we thought we weren’t doing enough for our young people.

“Suicide is the biggest killer among under 35s in the UK and every year we lose 200 school aged children. I never knew this, I was one of those people in ignorance who thought it would never happen to me and I would never lose a child to suicide. I did.

“When we finished we knew we had to do more so this is why we started a petition to have suicide prevention as a compulsory part of the RSHE curriculum in school, taught age appropriately and sensitively because we needed to tell young people this.”

The petition is still being discussed and talks are ongoing with the Department for Education with the issue selected as a key area within the Labour Party manifesto who unveiled a plan to reverse the rise in the number of deaths from suicide in May 2023.

Beth’s death was tragically part of a broader trend during the pandemic as many struggled with the impacts of the lockdown. But as causes remain so nebulous and suicide now being the biggest killer of people under 35 in the UK the issue remains as vital as ever today.

The Three Dads are set to kick off their latest walk from Stirling to Norwich in April this year as they intend to continue to raise awareness of Papyrus suicide prevention work to every corner of the UK.

Links

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this piece find support through the following action lines:

Samaritans: 116 123

Papyrus Prevention of Young Suicide: HOPELINE, 0800 068 4141, is a 24/7 line for children and young people under the age of 35 who are experiencing thoughts of suicide, and for anyone concerned that a young person could be thinking about suicide.

To donate to the Three Dads and follow their progress use this link.

To purchase the Three Dads book: 300 Miles of Hope use this link.

Featured image: the 3 Dads Walking, from left to right: Mike Palmer, Tim Owen and Andy Airey