New Office for National Statistics (ONS) data backs early University of Manchester study indicating the first national lockdown did not trigger a rise in suicide rates.

In April 2021, a study by researchers at The University Of Manchester found that suicide rates in England and Wales did not increase following the first national lockdown in 2020, despite higher levels of mental distress.

Their study, published in the April edition of the Lancet Regional Health, Europe, found there were 121.3 suicides per month between April and October 2020, after the first lockdown began, compared to a slightly higher rate of 125.7 per month between January and March 2020.

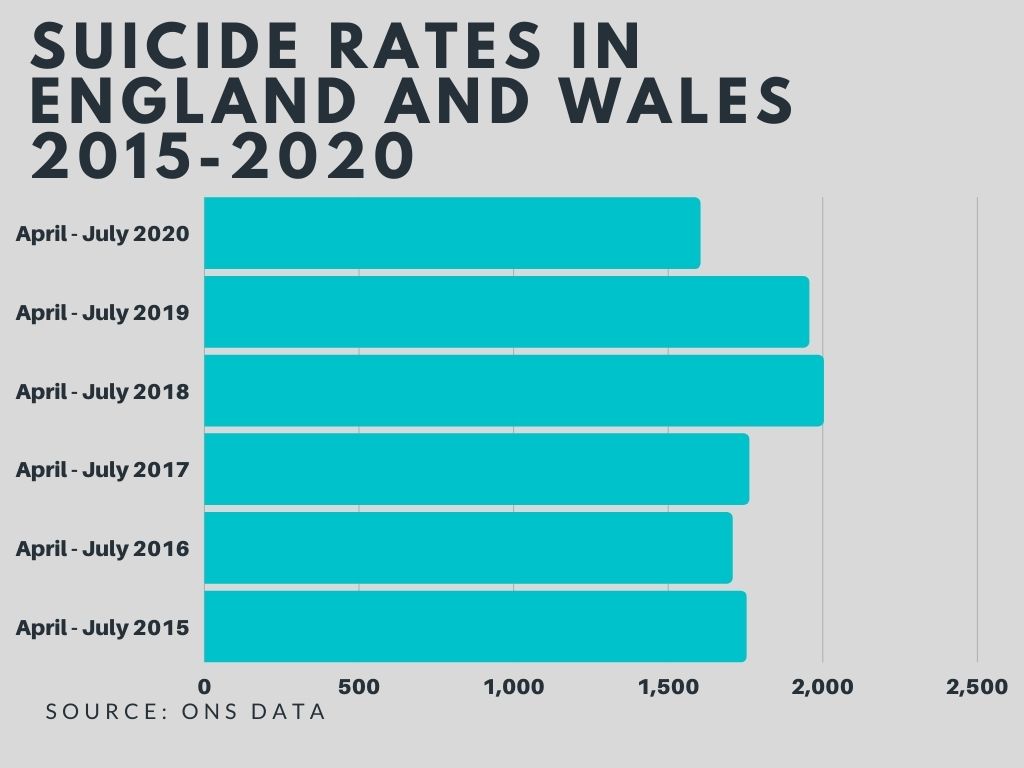

New ONS figures released on September 7, 2021 showed there were 1,603 suicides in England and Wales between April and July 2020, a sizeable decrease from the 1,955 in the same period in 2019, and fewer than the same period in the previous five years, with an average of 1,835 suicides between 2015 and 2019.

Both the study and the new ONS data provide evidence contrary to popular speculation that lockdown would inevitably cause a rise in suicide rates.

Study author Louis Appleby is Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) at The University of Manchester.

He said: “We didn’t find an increase in suicide rates in England in the months post-lockdown, although we know from surveys and calls to charities that the pandemic has made our mental health worse.”

He advises caution when interpreting the findings of the research, and the team stress the need to continue monitoring figures and to maintain suicide prevention measures.

MM spoke to John Junior, an ambassador for SOS Silence of Suicide charity, whose first instinct was disbelief.

“That sounds completely ludicrous to me,” he said, presented with the findings.

John, from Wilmslow, was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder in 2019, and has felt suicidal on multiple occasions throughout his life.

He takes crisis calls from people struggling with suicidal thoughts, and reports a striking increase in the number of distress calls he answered during each lockdown.

He described his own battle during the first lockdown:

“It was absolute hell for me, I was thinking about taking my own life and that was directly because of the lockdown.

“I felt trapped and suffocated by the restrictions, stuck inside my house, I couldn’t go out, couldn’t see my friends, couldn’t do anything, and I’m someone that relies on that routine for my mental health.

“I didn’t want to die, I just wanted that feeling to go, but I was saved and I’m so glad I’m still here to help other people.”

Study co-author Nav Kapur, Professor of Psychiatry and Population Health at The University of Manchester, suggests suicide rates may have been affected by supportive mechanisms of society itself, triggered when faced by extraordinary circumstances.

He said: “How can we square our finding that suicide rates have not risen despite greater reported distress?

“Suicide is complex, and rates do not simply follow levels of mental disorder. There may be a genuine social cohesion effect at the time of external crises – we’ve seen this in data from suicide rates around the time of the two world wars, suicide rates decreased and there is this idea that societies pull together when there’s an external threat.”

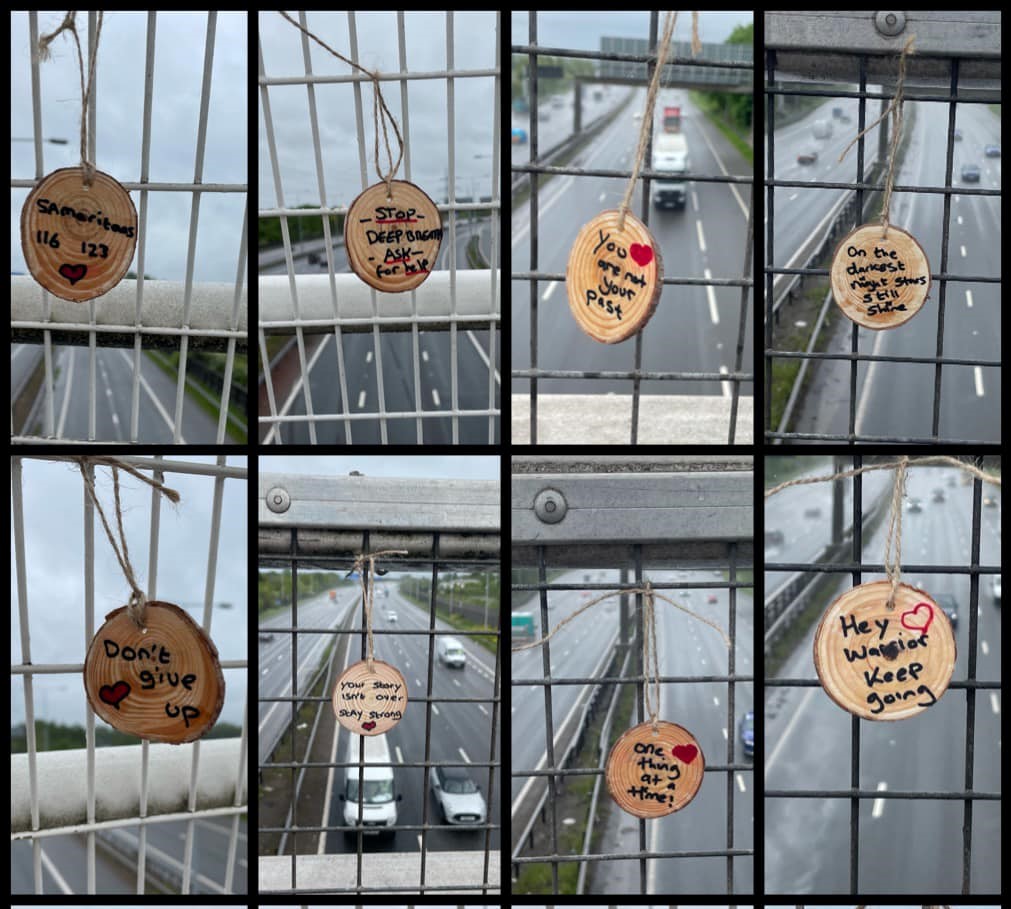

On reflection, John agreed that he had seen first hand how people have reached out publicly in support of mental health, sharing and opening up about the impact the stresses of this year have had on their mental health and wellbeing.

“Mental health went a bit more mainstream, after a few suicides had been reported early on and the media was saying there was a mental health crisis unfolding, I saw a lot of people posting support online to friends who might be struggling.

“The open discussion and awareness around mental health has been one of the few positives to come out of an awful year.

“Its so important to feel recognised .

“You see people posting and you don’t feel alone, you feel supported.

“Society has rallied around, and it’s definitely saved lives.”

Study co-author Dr Pauline Turnbull said: “While our findings show that suicide didn’t rise in England post-lockdown as many feared it might, we do need to be aware that it’s too early to see some of the longer-term impacts of the pandemic, such as ongoing economic adversity. It is essential that we maintain a focus on suicide prevention.”

Indeed, whilst welcoming the data as potentially reassuring, leading suicide prevention organisations call for caution in interpretation of the statistics, which only cover the period up to the end of the first lockdown, leaving rates from October 2020 still unanalysed.

Collecting data on suicide rates is also made problematic by a lag between deaths by suicide and their registration by a coroner, which can be more than a year late in some cases.

The University of Manchester team were the first researchers to use data from English Real Time Surveillance (RTS) systems in areas covering a total population of around 13 million.

RTS anonymously records suspected suicides as they occur, allowing early monitoring of figures before an inquest is held, though the team advise further development is needed before it can provide the full national picture.

Ged Flynn, Chief Executive of Papyrus Prevention of Young Suicide, said:

“The data from the Office for National Statistics suggests fewer deaths than in previous periods. That is always welcome news. However these are uncertain times and we must be cautious in our analysis, as the ONS itself suggests.”

PAPYRUS also warn a post-lockdown legacy of anxiety and distress could affect a generation of young people for months and years to come.

Flynn added:

“It is important to remember that while there is no reliable, statistical evidence of a link between lockdown and a significant increase in suicide, we do know more young people have been feeling lonely, distressed and struggling to cope with life.

“It is important that we all work together to keep our communities suicide-safe and that young people know they are not alone and that help is available.”

Jacqui Morrissey, Assistant Director of Research and Influencing at Samaritans concurred:

“The latest ONS data shows that considerable work is still needed in tackling suicide, with someone’s age, and even where they live, significantly increasing their risk of dying by suicide.

“Whilst on the surface it may seem reassuring that the pandemic has not increased overall suicide rates, the picture is not straightforward due to the delays in reporting caused by covid-related disruption and we must not become complacent.

Morrissey calls for a more effective nationwide system for collecting reliable, comprehensive, real-time data on suspected suicides.

This data would ideally include age, sex, ethnicity, sexual orientation, as well as information that relates to risk factors such as occupation, history of mental illness and contact with services.

This would help to monitor and respond rapidly to any increases in suicide rates, particularly within certain groups or an area of the country, and ultimately save lives.

She added: “Any life lost to suicide is a tragedy and we know that the after-effects of the extraordinary last 18 months will continue to impact people’s lives in the years to come.”

If you or someone you know needs help, call Samaritans free on 116123,

or contact PAPYRUS HOPELINEUK on 0800 068 4141, text 07860 039967, or email [email protected].