Women are projected to have most of their children post-30, but it may not necessarily be out of choice. As many feel the pinch of the cost of living, financial stability and career progression have become priorities while having kids may now be somewhat of a luxury.

Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has compared four cohorts of women born in the years 1923, 1951, 1978 and 2007, and found that the age women are having kids has increased.

And is continuing to increase.

While 82% of women born in 1940 had their first child by 30, this almost halved to 42% by 1994 and saw a move away from women having children in their 20s.

For those turning 18 this year, the trend is projected to continue and they are expected to have fewer children than their mothers and grandmothers. There is a clear picture being painted here of older mothers with fewer children. But why is that?

The cost of surviving

With the price of a Freddo reaching an all-time high of 30-35p in most supermarkets – the future is uncertain. Instead of childbearing, balancing rent payments and inflated food costs are taking precedence and causing women to hit pause on having kids.

Maddie, a 25-year-old who works for the NHS, said that she would ‘need to be much more financially stable’ for her to even consider having kids.

“Whenever I talk to people about having kids, money does often come up in the conversation. Usually it’s more in relation to a modern attitude of not wanting to spend all your income on your children, and being able to maintain some luxuries in your own life, rather than it being an outright deterrent,” Maddie said.

Financial pressures are fostering a growing consensus amongst young women that you simply cannot have it all.

Pessimism aside, this is not necessarily the case for everyone. And Maddie points out that she knows many people her age ‘who have already started families despite being on lower incomes’.

However, the recent childbearing report by the ONS found that only a mere 4% of women born in 2003 had a child by age 20, and that fertility rates at this age have been on a sharp decline since the 70s. With the 40s and 50s showing the highest rates of women giving birth by age 20, women are struggling to achieve stability as early as their parents and grandparents did.

Jess, a 23-year-old NHS physio based in Oldham, said: “Many Gen Z adults are dealing with student debt and job market instability – especially after the pandemic. Unlike past generations who could often support a family on one income, today it feels much harder to reach that level of financial security before even thinking about having kids.”

With a cat and mouse game of low wages and high rates of inflation, we have to ask whether having a child is becoming less of a choice and more of a luxury for the financially stable?

iPad babies and the dangers of social media

Whereas parents in the past would have given their kids a colouring book and pens in a restaurant, this has now been replaced by iPads, tablets and anything with an internet connection that can keep a screaming child occupied.

Born in the 1950s, Carol from Wigan was married and had her first child by the time she was in her 20s. She said: “Everything is costly now. Children have to compete with each other for material possessions, putting pressure on parents. Years ago, all kids wore similar clothes and footwear – unlike today when they all want expensive name brand clothing and footwear, phones, laptops and game stations.”

In agreement with this, Maddie said: “The experience for our generation is really quite different than that of our parents. Most kids will have a mobile phone by the time they reach secondary school, and it’s much harder to keep kids safe from harassment and harmful material.

“I worry that my kids will be raised in front of a screen, and what effect this would have on their development.”

While the depictions of social media’s influence on young minds in the recent Netflix show ‘Adolescence’ may have been a shock to some, it is far from a recent phenomenon. And for a generation of 20 and 30-year-olds who know social media platforms like the back of their hand, they are very aware of the dangers that their kids will face.

Buying a house AND having kids? In this economy?

In 1977, an average of 26% of women would have had a kid by the ages of 23 to 24, but for those born in 2001 only 11% had a child by the time of turning 23 – less than half as many.

This year, 23-year-old student Caitlin turns 24 – the same age her mother was when she had her. Yet by her age, her parents already had a house. This is not the case for Caitlin – nor the majority of those in their 20s, and getting on the property ladder seems to be an impossible feat.

Caitlin, who mentioned she doesn’t want children at all, said: “The majority of my friends rent, and there is no way that they could afford to have kids because their rent is so high.”

That said, it comes as no surprise then that there has been a sharp decline in live births by the age of 25. At its highest in 1940, 208 children were being born per thousand by age 25, but this more than halved by 1985 to 93 live births per thousand. Continuing to decline, this has reached 66 per thousand for those born in 1995.

Live births by age 25 are projected to drop so low in fact that they will almost match the levels of live births by women aged 40 in coming years.

Building a career and battling maternity leave discrimination

Women born in 1978, on average, have had one child by age 31 according to the ONS. But for their mothers’ generation, born in 1951, this would have occurred younger – by age 26.

“We were brought up with the mindset to have children early. Teachers would even say to most girls that there was no use studying, as girls are to get married and have kids while the men go out to work, or study,” said Carol. Who also admitted that she was ‘too young’ to have had kids when she did at age 20.

In the 21st century, a well-paid career is not only preferable, it’s becoming essential.

“I think many more professional women want to carve out a career and have some stability before risking being tied down with a partner and having a family, which makes more sense than rushing into having children and struggling to provide for them,” Carol said.

Cara, a 35-year-old queer woman and founder of a startup said she would happily wait until 45 to have kids. For her, a stable career is currently more important than having children. “It would impact my ability to work certain hours, and impact how I am viewed in my role. As well as my commitment,” Cara said.

There is also a level of maternity discrimination for those who do become pregnant while in their role.

As recently as March this year the BBC reported that Maeve Bradley, an assistant vice president at Citibank in Belfast, was excluded from a promotion during her maternity leave. Instead, her firm promoted the person who had covered her time-off. She then went on to accept £215,000 in a discrimination settlement.

This is a brutal reminder that the battle is not won even if you do have a good career and financial stability.

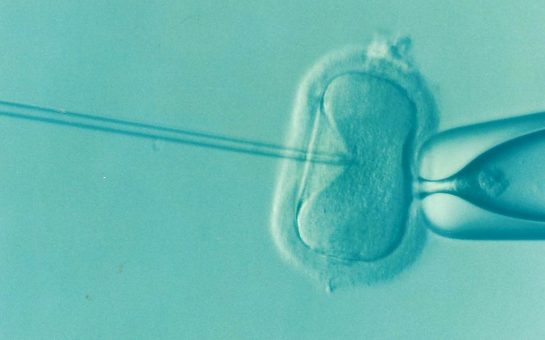

What if we leave it too late?

Women born in 2007 are projected to have more children over the age of 40 when compared to their mothers. But as women wait to own a home, or at least be able to comfortably pay rent, there is the risk of leaving it too late.

A study conducted in 2016 found that women experience a significant reduction in their ability to reproduce in their late thirties, and also show signs of increased risks of infertility.

Maddie said: “I think as a woman if you leave it too late your chances of being able to have children do reduce somewhat as you get older.”

Despite this, the likelihood to conceive will differ from one woman to the next, and for some they are already at a disadvantage. Lana, 25, who is studying for her PhD, felt that having kids would put a strain on her education and professional development, but recently she discovered that this is not the only factor she needs to battle.

She said: “I found out I only have a 20% chance of having kids. I wasn’t even sure if I wanted them, and I wanted to adopt anyway, but having the choice taken from me is definitely very confusing.”

Likewise, for queer women such as Cara, there is the added issue of finding alternative solutions. “I would need fertility treatments if I was to birth a child as I’m queer, and also older. Either this or adoption, which can take years to plan for,” she said.

According to other data recently released by the ONS on the number of births in England and Wales, birth rates are indeed declining. And in 2023 we saw the lowest number of live births on record since 1977 at 591,072 live births.

So, women can’t afford to have children younger, and having them older may decrease their chance of pregnancy – what happens now? Well, the only choice left may be to not have them at all.

Source: Childbearing for women born in different years, England and Wales: 2023 – ONS

Feature photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash