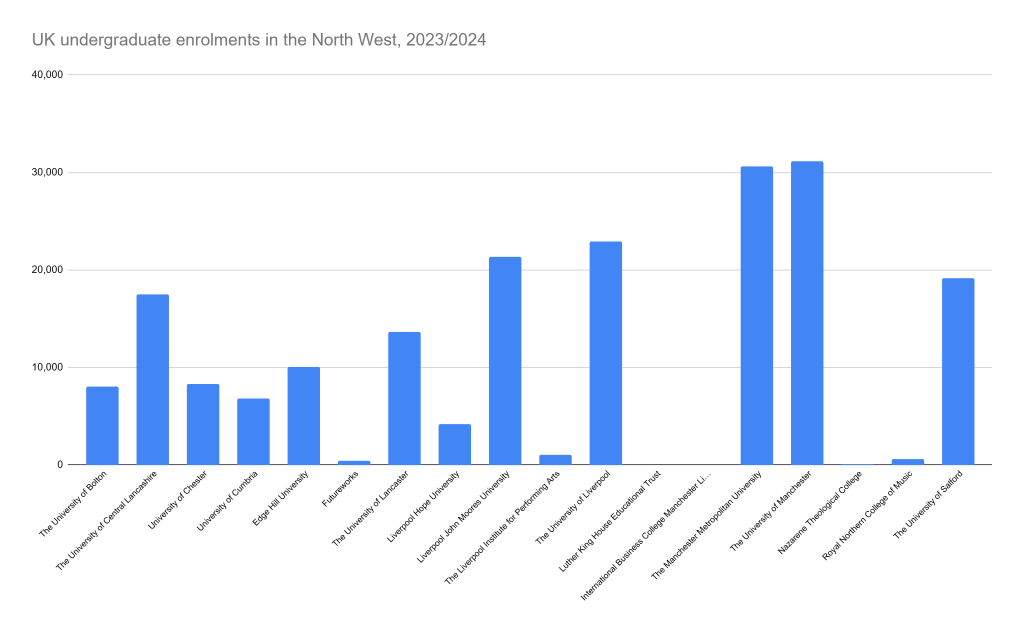

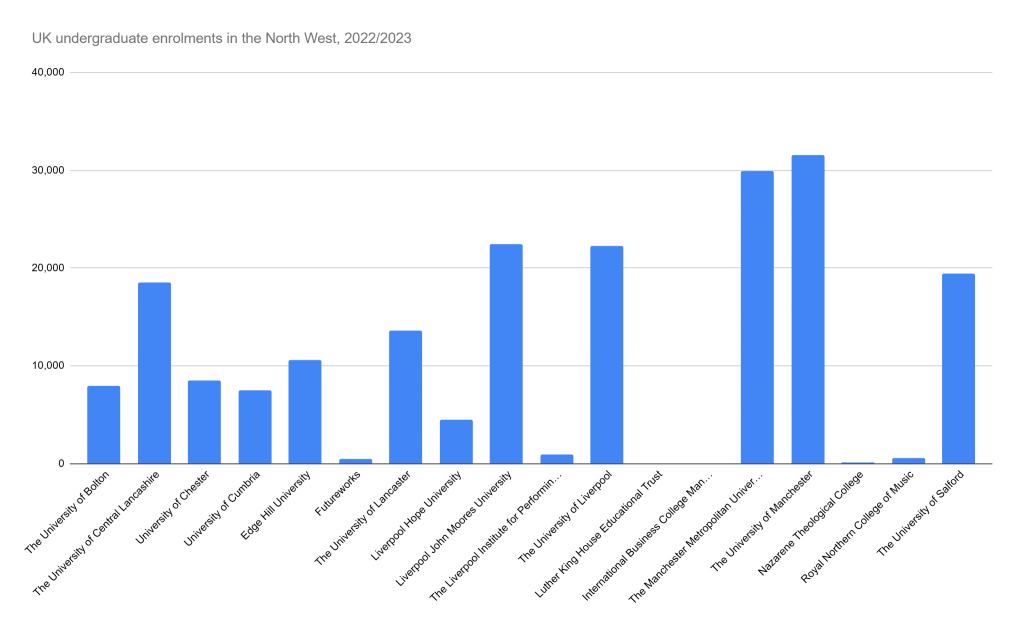

UK universities saw their first decline in student enrolment rates in nearly a decade in the academic year 2023/2024.

The overall decrease was 1.1%, with a greater decline in the North West of England, which from 2022/2023 to 2023/2024 saw a 1.5% decrease in all undergraduate enrolments.

This is according to recent data released by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) that collects data about higher education (HE) in the UK.

It shows that compared to the 198,775 undergraduates enrolled in the North West in 2022/2023, only 195,980 enrolled in the same region in 2023/2024.

Source: HESA

Currently there are no definitive predictions about 2025 university enrolment rates in either the North West or the wider UK, but the fall is expected to continue in the coming years.

The reasons for the downturn include the cost of living crisis, student debt, rising mental health issues amongst young people, an over saturated job market and a 7% reduction in international student numbers in 2023/2024, due to recent changes to UK visa policies.

From January 2024 stricter rules about dependents of international students were implemented, meaning foreign undergraduates can no longer bring their families to the UK. Since then, major declines of students coming from counties like Nigeria, India and China have been spotted.

Another attribution regarding the drop is a growing prejudice towards “Mickey mouse degrees” (typically regarded as arts or humanities subjects) that some consider a hinderance to graduates and of little use in the business world.

Catherine Fox, lecturer and academic director of the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University, says: “I think the decline is patchy and varies from subject to subject and university to university.

“I strongly believe we need to push back against the idea that, for example, English and Creative Writing degrees are somehow less useful to wider society.

“Humanities degrees have a range of transferrable skills that are highly sought after by employers.

“And to assuage fears about debt, I think the government could re-think how student loans are structured and whether there is a more equitable way of collecting loans through tax codes.”

Grievances surrounding HE are echoed by Amara Patel, 20, who started at MMU in 2023 to study for a BA (Hons) Creative Writing degree.

“I was really excited, but by the end of my first term I wondered if I’d made a mistake. Most people never come to lectures because they’re working or hungover. The lectures I do go to I often think suffer from lack of participation.

“School really pushed university on us but my dad felt that attending university was just more of the sausage machine that education has become and I kind of wish I’d listened to him and maybe gone travelling or gotten a job.”

Another MMU undergraduate, Nathan Partridge, 23, agrees.

“I travelled after leaving school for a few years, which was great, but I had FOMO about uni.

“I’d met British people abroad who had opted out of going altogether and others who had gone. I heard both sides of it, some feel that the expense isn’t worth it, and some people would rather have the university experience than always wonder “What if?” I chose to go.

“I enjoy my degree, but a lot of the time I’m learning alone in my room with my laptop and I wouldn’t recommend that to many people.”

So, why is this a cause for concern?

Although student dissatisfaction and a 1.1% enrolments decline in 2023/2024 might seem minimal, it is predicted to continue, and could lead to serious long term effects for the UK.

Universities generate income for many jobs in the local economy (nightclubs, pubs, other typically student populated businesses) and therefore if HE centres start to fail, local economies are affected too.

There is also the fact that in some parts of the UK (typically the South East), HE is the second or third largest employer after the NHS, so a university collapse could mean loss of jobs on an enormous scale.

And in global terms, a consistent decline over a significant number of years could potentially damage the UK’s international reputation and cause considerable gaps in the public and workforce’s skills and knowledge.

And what does this mean for the country?

A population with a decreasing number in HE will mean the UK job market will have to adapt considerably and shift towards preferring vocational training, potentially rendering HE redundant.

Worryingly, a decline in university enrolments could also mean less graduates entering research roles, potentially slowing down the progress of essential fields like medicine.

HE also promotes social mobility, so a reduction in undergraduates could cause the UK to suffer socio-economically.

There is also the risk that a drop in international students could impact the UK’s GDP and cause economic problems.

Whilst the effects are profound, globally and in the UK, long term and short term, Catherine Fox remains hopeful about the future of HE and praises its virtues.

“I still firmly believe in the experience of studying for the sake of studying.”

“The experience of a kind of ‘licenced irresponsibility’ where you are free to discover yourself aged 18-21 in a safe environment can be transformative.”

Photo: Lucinda Walton

Source: HESA

Main image credit: Lucinda Walton