The number of British adults experiencing symptoms of depression has doubled since before the Coronavirus pandemic, according to new data collected by an ONS survey.

In June 2020, approximately 1 in 5 adults (19.2%) were experiencing moderate or severe symptoms of depression – a figure that has doubled since the 9 months between June 2019 – March 2020 (9.7%), with women aged 16 – 39 who could not afford unexpected expenses affected the most.

Symptoms of depression were measured using an eight-point Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) that was issued to the same 3,500 adult patients, both before and during the pandemic.

Tim Vizard, Principal Research Officer at the Office for National Statistics explained this sampling method, saying “revisiting this same group of adults before and during the pandemic provides a unique insight into how their symptoms of depression have changed over time”.

From this, we can distinguish how much influence the pandemic has had on the same individual and their experiences of depression. We can also examine different characteristic groups to identify national trends.

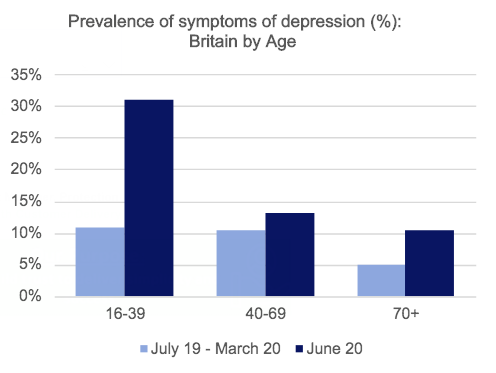

A key trend presented in the data is that young people were disproportionately more depressed during the pandemic than before.

Whilst there were consistent increases in depressive symptoms across all age groups, 21% more people aged between 16 – 39 reported depressive symptoms during the pandemic. Meanwhile 2.6% more people aged 40 – 69, and 5.3% more of the over 70s demographic reported worsening in depressive symptoms.

“It may be the fact that they have been living on their own, so if they’ve not got someone to talk to or can’t see family or friends”, says Susan Carr, a Manchester-based Counselling Directory member who is currently supporting clients via video sessions.

“I have [also] spoken to some younger people who have moved back home so they are not on their own and they are facing the challenges of being in that home environment or working in a bedroom – there have been those sorts of difficulties”.

This prevalence of depressive symptoms amongst young people is likely due to several factors including job insecurity that exists at the start of young people’s careers.

Additionally, when educational establishments, restaurants, nightlife, and travel were no longer available, young people would have felt more isolated than older patients who are more likely to have spouses and families for support.

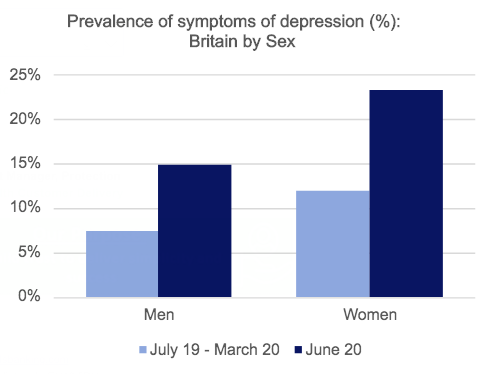

Whilst women reported higher rates of depressive symptoms both before and during the pandemic, there was still a larger increase in the number of women reporting these symptoms (11.4%) than men (7.5%).

This would imply that there are gendered differences in the impact that the pandemic has had on the population.

Susan believes that there are many reasons for this, such as the stereotypical pressure for women within the household to take on domestic and child-rearing roles, whilst also having to work from home.

She also notes that there is perhaps more job security in male-dominated industries such as Finance or Technology where there might also be better structures in place to accommodate working from home:

“Women have also fallen into those jobs that have been more hit by lockdown where there might be more uncertainty about whether you are in a job or on furlough, such as hospitality jobs. That does play into those being more susceptible to depressive symptoms”.

Whilst job security is not necessarily a root cause of depression, it can be a catalyst that heightens existing mental health difficulties.

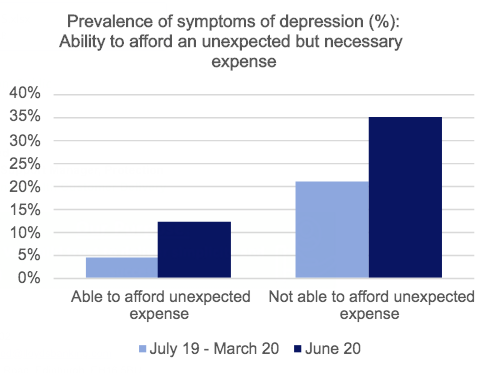

ONS findings show that the inability to afford an unexpected but necessary expense generally results in higher rates of depressive symptoms, but there was a 13.8% increase in people reporting these symptoms during the pandemic, compared to the 7.8% increase amongst those who can afford such expenses.

“It’s when all these different things intersect, so not being able to afford an unexpected expense, you are more likely to experience those depressive symptoms if you’re experiencing financial difficulties.

“It leads on to: Can I afford my expenses? Can I afford my mortgage? Will I have to move house. It’s not just one area of your life that is affected if your job goes […] those areas of stability are affected too”, explains Susan.

Tessa Schiller, 25, falls into the group of young women who are statistically affected the most. She currently feels the ‘lowest she has ever been’ and has sought out counselling for the first time in four years, as a result of the difficulties brought on by the pandemic.

“I think there is, in the back of your mind, the feeling that I’m so young I’ve never really had to solo deal with a financial crisis before. So knowing that there’s one on the horizon and I’m still relatively fresh in the working world does mean that I feel a little less secure than I’d like to”, says Tessa.

“I went from living my best life in London, being busy at work and out most days, to living in Norwich, which was a ghost town. It was just quite a brutal hit of several big changes to lifestyle at once and I found that hard to cope with.

“I wasn’t furloughed at any point but did work in an industry that was severely hit by the situation. So whilst work was an incredibly supportive working environment, my job hasn’t exactly been the most positive one”, she adds.

Not only does Tessa cite the change in lifestyle pace as a key contributor to her depressive symptoms, but she also feels that the general tone of melancholia has affected the entire population, meaning that even those she would turn to during a difficult time aren’t able to provide the same support they used to.

“I think there’s a total loss of community, I feel very isolated because everyone is struggling, so in a way, it’s almost harder to lean on people than it was before” she explains.

“I’ve noticed women are more collaborative in their approach to dealing with mental health. As a stereotype I think it’s true that women just tend to be more open and honest about stuff and so maybe that [loss] of the support network we’ve painstakingly built up, impacts women so much more”, she adds.

The fact that there is a national mental health decline is not an unexpected outcome of a global pandemic, it is a rational response to such seismic change; in April, the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy wrote to MP Nadine Dorries, Minister for Mental Health, Suicide Prevention and Patient Safety, to share their petition urging the Government to maximise the role of counselling and psychotherapy during this time.

But Susan highlights the fact that counselling sessions, through the medium of video and telephone, are not the same: “For some people, even though they do therapy remotely, they physically haven’t got a confidential space or environment where they are able to have their appointments”.

Whilst we must be careful to distinguish a depression diagnosis from depressive symptoms during a difficult time, it is clear that people, particularly young women, require more mental health support than before.

As winter approaches and depressive symptoms rise as a result of those who suffer from Seasonal Affective Disorder, the already strained NHS may observe a further increase in those seeking mental health support to alleviate their hardship.